One day, in 2018, I was looking at Twitter. Then, this popped up on my feed:

Don’t really have words for this moment.

— TOMI (@tomi_adeyemi) February 7, 2018

Have officially held my first book.

I cannot wait to share #ChildrenofBloodandBone with you all in 30 days pic.twitter.com/JWdaFe1PiW

This was the first I ever knew of Tomi Adeyemi. Her reaction was so true it stuck with me, so I finally got her book and IT WAS AMAZING. It’s full of pride, and terrible heartbreak, and hope, and it’s hard not to imagine that this same story could happen in American streets today, except for the magic part.

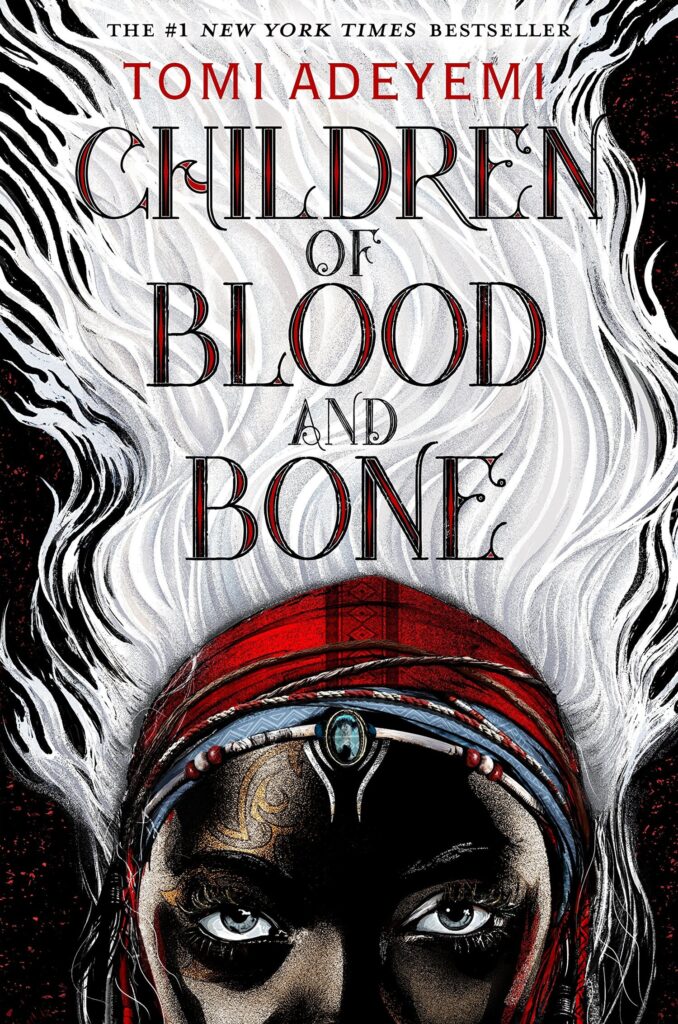

Children of Blood and Bone is the first book of the Legacy of Orïsha trilogy by Tomi Adeyemi. The protagonist is Zélie Adebola, a teenaged divîner living in a society where anyone with white hair, indicative of potential magical ability, is oppressed. She lives with her father and brother Tzain, and as a child saw her mother get rounded up with all the other maji in her village, tortured, and hung up from a tree. This marks every one of her thoughts and actions.

Zélie is seriously traumatized, she makes a lot of very important mistakes and she’s aware of the pain they cause her family. It’s hard for me to see her make the wrong decisions because I want a reprieve for her. A big theme in this book is survival, it’s hard to move forward when your hope for something better keeps you from doing what needs to be done. All the characters have a very raw and dark side because of the price they’ve paid for their survival, but still they try to do what’s right.

Another theme is redemption and finding your true self. This is strongly reflected in Amari and Inan’s storylines, they are the children of the King who ordered the destruction of all maji. Inan is supposed to be strong as the next king, but he is terrified of making a mistake. Amari has never been outside the castle. Their father has tried everything to protect them and make them strong, but he is horrifyingly abusive and has scarred them both physically and emotionally. Amari acts bravely essentially by instinct, which creates a huge dissonance with the belittling way she sees herself. Inan is confused by his wants and his duty and it terrifies him.

This book is a great example of how to write a Black-centric story. Objects are referred to by their West African names, like the gele and dashiki, without explanation or description. This leaves it up to the reader to get educated instead of forcing the writer to explain, thereby trying to justify their “otherness.” It constantly challenged my ingrained racist assumption that a royal family must be white in a fantasy book. As a White-presenting Latinx immigrant, I have my own assumptions to challenge along with the ones from where I live, and I’m glad for it.

The book holds a mirror up to current events in the US in the way it presents caste, class and race. It’s impossible not to see the parallels between the book’s violence and unbearable injustice and the real world’s police brutality and systemic racism. If your race identity doesn’t fall within the Black or Brown community, I recommend reading these types of stories to develop empathy for those who live these situations in real life.

As far as writing style, I do think Ms. Odeyemi’s character voices get muddled together, I can’t tell whose chapter I’m on because they all sound very similar. This is her first book and I’m more than willing to see how she grows as a writer, I’m excited to see where she goes. She did a great job world-building, her portrayal of pain and joy are pure and painful, and it is imperative that we support Black writers that tell Black-centric stories.

Now let’s rise.